By James Peacock

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been no shortage of discourse about the ways that society as we know it has been irreparably altered. Most of this has dealt with matters in the adult world, but what about the ways that the lives of America’s youth have been altered? One particularly informative way to assess what has changed is through the lens of youth sports in the United States.

An investigation into that youth sports system revealed deep fragmentation, plagued by a decline in participation rates, socioeconomic stratification, and a full-blown mental health crisis. As was the case in many other parts of society, the COVID-19 pandemic simultaneously exacerbated already existing issues that had (for years) gone unaddressed and created new problems as well. Given the abundance of problems we face in our time, it is not a surprise that issues in the world of youth sports would be relegated to the societal periphery. However, issues currently being faced by our young people in the short term will have wide ranging long-term effects. Given the way in which sports have often served as a reflection of the health and vitality of our democratic society, we must take constructive steps to address these challenges head-on.

I: Participation Trends: Who Got Left Behind?

In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 brought the entire world to a screeching halt. Businesses closed (some permanently), schools sent students home and attempted to soldier on in the newfound world of Zoom, and professional and collegiate sports paused their seasons or cancelled them entirely. In a time where an invisible disease which wrought illness and death seemingly lingered around every corner, no part of society was spared from mitigation efforts. Though much of the world has returned to some semblance of pre-pandemic normalcy, participation and engagement in youth sports across the board have had a more difficult time rebounding.

“I think the biggest issue is in the months and years lost, with no contact and playing sports. Children lost the ability to practice and or just play at all. Now, in observing in our programs the levels at which children should be participating, they fall short,” says Andrea Russo, the head of the Department of Recreation in Pound Ridge, New York.

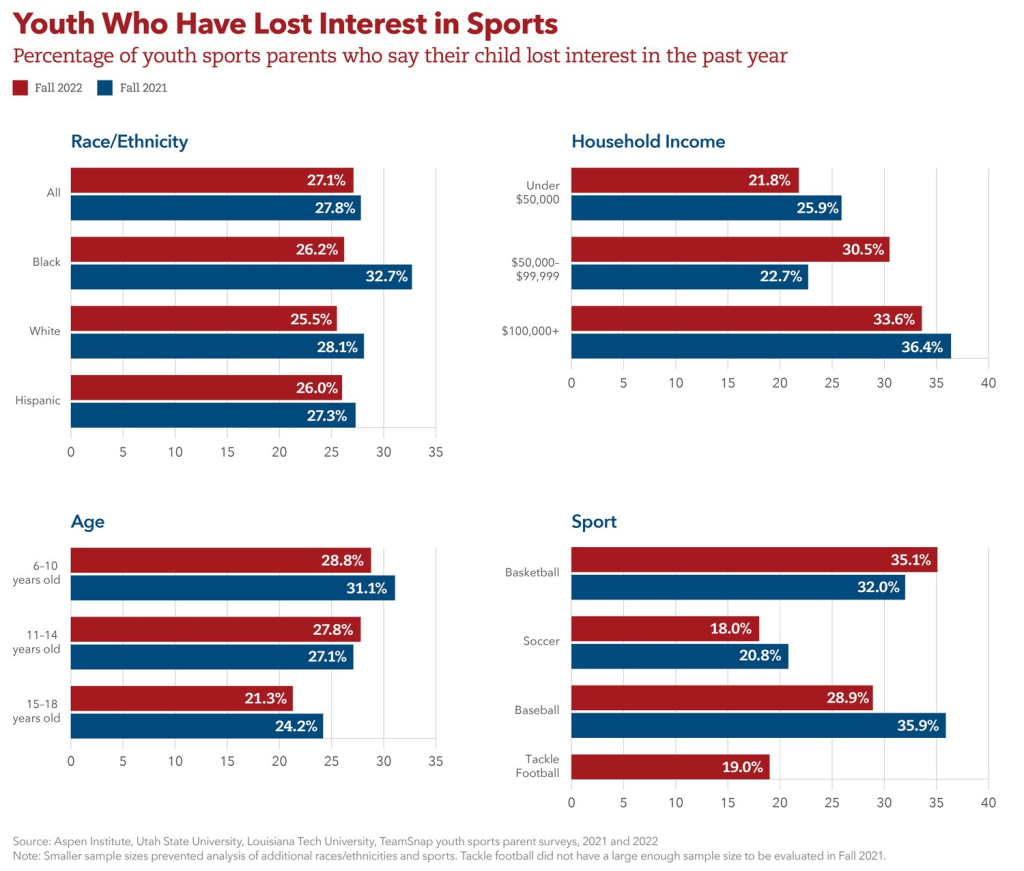

Indeed, the Aspen Institute found that, in 2022, youth participation in team sports remained at a “historically low” level. For some children, the absence of athletic commitments during COVID was something of a liberating experience, and they decided that they were better off without organized sports in their lives. The rate at which these children have lost interest in playing sports in the past two years is startling. This is reflected in the graphic below, courtesy of the Aspen Institute:

“Prior to the pandemic, our middle school sports programs had been struggling for years, and COVID only made things worse. We basically lost a full year of athletic growth for most of our students as they were locked down in their homes,” says Joe DiMauro Jr., a middle school physical education instruction in Bedford, New York, “very few kids were able to maintain the same level of sport participation throughout the pandemic. Now, many students feel they are behind athletically and are not comfortable starting back up and joining our modified school teams.”

This is where it is important to discuss the impact of technology in this participatory equation. While some children, particularly those in neighborhoods with significant amounts of green space outdoors and where crime was not a concern, were able to maintain some level of meaningful physical activity, others only had technology to turn to. It is not a secret that the ever-increasing prominence of video games and social media have contributed to declining rates of participation in youth sports, or general engagement in physical activities.

“Organized youth sports have never done the research that they need to do to draw kids in and keep them in. Social media and phone games run tests, do their homework and have algorithms that keep kids engaged. We’ve never talked to kids about what changes they’d like to see in their sports, or what sports they want to play. The videogame people have that mastered,” says Dr. Jay Coakley, a sociologist who specializes in youth sports.

Figuring out how to counter the effects of these technologies will be crucial in the effort to bring children back into organized sports. Likewise, much thought and consideration will need to be devoted to the broader question of why more kids are losing interest in organized sports in general. Participation rates were in gradual decline prior to COVID, and though they are beginning to bounce back, this should still be cause for concern.

Aside from the desire of children themselves to participate in organized sports, one question that must be answered is whether there are even enough adequate and affordable opportunities available to them in the first place.

II: Socioeconomic Stratification: The Have’s and The Have Not’s

As was the case in virtually every aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic, wealth and socioeconomic status were major factors in terms of who felt the worst effects of the pandemic, and who was able to weather the storm. Youth sports were no different in this regard. Well-endowed, privately paid for programs were able to stay afloat and even prosper, while programs funded by public money suffered tremendously.

“During the pandemic, some families that had money could continue playing sports. They traveled to different states to play in tournaments if their state had sports shutdowns. Lower-income families could not do that,” says Jon Soloman, editorial director of the Sports & Society Program at the Aspen Institute.

“Pay to play programs became even more dominant during and after COVID, and right now, many of those recreation programs that didn’t have consistent funding and the support of major organizations, have had a hard time getting back together,” says Dr. Coakley, “COVID accentuated the division between the high cost pay to play programs and the low-cost recreation programs.”

The youth sport programs that have been most harmed by this trend are the ones that are administered through local parks and recreation departments. They are often funded by tax-payer money and administered by parents and other adults in the community willing to volunteer their time and services. Such programs have been especially important in lower-income communities because the only “barriers” to participation are modest registration fees, and the cost of the necessary equipment to participate.

Sometime in recent years, the prevailing sentiment began to view such programs as a less efficient means of allowing children (and their parents) to achieve various goals in athletics, such as receiving a college scholarship to play their respective sport. Parents have been incentivized to believe that the more money that they put into their child’s athletics, the more that they will get out of it on the back end. While this segmentation has benefitted those able to afford it, it has also had the effect of “pricing out” countless families who simply cannot afford the costs of travel, registration, training, etc. Post-COVID inflation has only made participating in such programs less attainable for more families.

According to the Aspen Institute, in their annual “State of Play” report for 2022, families who have a household income of $150,000 or more spend nearly four times the amount of money on one child’s primary sport (per season) than families making less than $50,000 dollars. These economic disparities can also be observed along racial lines, as white families spend $300 more on one child’s primary sport (per season) than black families. Simply put, youth sports have increasingly become a system whereby the “elites” can insulate themselves from those families with less money and have created a “pay for play” system that is seen as more desirable, and largely self-sustaining.

“Local programs used to be funded publicly through parks and recreation departments, all through tax money. The cost per player was minimal, if not free. I don’t see those coming back, unless there is a major political change in the United States. The people who are relatively wealthy have created programs that reflect their own interests, and they are not going to leave those programs,” says Dr. Coakley.

III: The Pandemic and Youth Mental Health: Children Are Struggling

Aside from the pure physical toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps the most destructive effects on young people and the public at large can be seen in mental health. As has often been the case, the pandemic exacerbated already existing problems in the mental health of children and young people, creating a full-blown crisis (as indicated by the CDC):

Such findings have been far from limited to the CDC, as the National Institute of Health last year concluded that,

“The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents is multifaceted and substantial. Survey studies regarding child and adolescent mental health amid COVID-19 indicated that anxiety, depression, loneliness, stress, and tension are the most observed symptoms.”

The lack of availability of organized sports during the pandemic contributed to these alarming trends. For many children, organized sports serve not only as a means of socialization with other children, but also as a means of exploring identity. Organized sports offer life lessons to children about the importance of teamwork, sportsmanship and accountability. Though such lessons can be replicated in other kinds of activities, very few offer them in tandem the way that sports do. Another, perhaps lesser explored benefit of participation in organized sports is in the ways that it benefits the relationships built between children and adults:

“One thing that is so key that sports provide is that there is a community of caring adults around them who will support them in all contexts. Adults become important caregivers to kids, and during COVID, their circle of caring adults became much more constrained,” says Maryam Abdullah, a child psychologist for the Greater Good Science Center, “[in not] learning that there are other trusted adults in the community, that was a lost opportunity for children who were deprived of opportunities to participate in sports.”

Organized sports also, for many children, serve as a means of escape from problems that may be plaguing their home life. The pandemic served as the first time that a lot of children had to deal with feelings of profound grief. Some lost family members, others had parents who lost jobs and whose stress and anxieties permeated their children’s lives, and others still were faced for the first time with real-world issues that were simply inescapable. Children were faced with a situation where they had nowhere to turn to alleviate their stresses and feelings, and that has shown.

As children have returned to playing fields across the country, there has been a greater impetus on coaches and administrators to be more nurturing to the needs of children.

“If sports aren’t delivered properly, such as coaches or parents not making the experience fun and applying too much pressure on youth, this can hurt the already fragile mental health for some youth. Too many children don’t see sports as a place for them. They don’t feel welcome, they don’t believe they’re good enough to play, and in some cases, sports can be a toxic culture. That has to change,” says Jon Soloman, “coaches can play a significant role by better understanding how they communicate with athletes can make a difference, including providing safe spaces for youth to feel like they can talk about their problems.”

“Coaches are in a position to observe any changes in children’s behaviors that could be signs of something that they can explore further. It’s important for coaches to be on the lookout for signs in children and have a conversation with them, to show them that they care,” says Maryam Abdullah.

This paradigm shift in what is required from coaches and adults in their relationships with young athletes is not something that can or will happen overnight. It is going to require a systematic restructuring of the ways in which coaches are taught and trained to be coaches. No longer can the focus simply be on X’s and O’s and how to win games. Far more important than the win-loss records are the mental wellbeing of the children who are participating in organized sports.

“Young people have greater mental health needs now than they did prior to COVID. But it’s not just COVID, it’s the uncertainty that they see regarding their own futures (climate, crime, ability to buy a house, ability to get into a good school, etc.),” says Dr. Coakley, “any parent would buy into a program that said, ‘we’re going to be sensitive to your children as human beings, and we’re going to treat them as human beings, rather than little machines to benefit us as coaches.’”

IV: What Does This All Mean?

When viewed in totality, the picture of youth sports in the United States, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, is one of uncertainty.

Though there is evidence that participation levels are returning to where they were prior to the pandemic, coaches and administrators alike will still have to find a way to reengage those children who either lost interest in organized sports or those who suffer from a lack of confidence after such time away from sports. It is up to these administrators, particularly those working in recreation departments across the country, to look at what today’s kids find interesting and engaging generally and find a way to implement that into their sports. Children today have seemingly unlimited options to occupy their attention, so it needs to be impressed upon them that a healthy and constructive way to do so is through participation in organized sports.

This effort, particularly on the part of local communities, is likewise perhaps the only plausible way to try to counteract the movement towards a youth sport structure that is highly segmented and exclusive. Sure, the “pay for play” system benefits those who can afford it, but what about those who cannot? Are we supposed to simply accept a future when all college scholarships are doled out to the children of the 1%? There must be a concerted effort from the top-down to prioritize, fund, and advertise local sports programs that are publicly funded. There is a massive pool of children out there with the skills and drive to participate and excel in sports, but there need to be ample opportunities for them to do.

In terms of adjusting the youth sports structure for an era in which children’s mental health is finally receiving the recognition and prioritization that it deserves, much of that responsibility will fall to parents and coaches. Organized sports offer such an abundance of not only physical, but also psychological benefits for children and young people…if they are administered correctly. All children should be made to feel that their local organized sports are accepting and empowering, allowing them to learn important life lessons, allow them to learn more about their respective identities, and allow them to further their process of socialization.

Likewise, the way that coaches are trained, and the responsibility that they must be willing to take on, must also be adjusted. Coaches are in a unique position to serve as sounding boards for children, especially those who may not feel comfortable discussing their mental health struggles with their own parents. Coaches are not psychologists, but they must be at least trained to show children that they care about them, and that their athletic experience is about much more than wins and losses.

The COVID-19 pandemic should have served as a wake-up call for all the things that are wrong or need to be corrected in the American youth sports system. Whether or not the adults involved have received the message, will be everything in determining what exactly the future of youth sports, and therefore the future of America’s youth, looks like.